This is a first in a series of cool linguistics stuff. Also checkout my blogs on Math and AI as well.

Writing Systems

Introduction

Writing Systems are also known as orthographies. You already know at least one - the Latin alphabet, which you’re reading right now. Here’s an overview of how all the different writing systems work.

Phonetic Orthographies

In phonetic writing systems, symbols are written based on sound. For example, in the Latin alphabet, the word “cat” is written with a “c” for the “c” sound, “a” for the “a” sound, and “t” for the “t” sound. Of course, it’s not always one-to-one, or even consistent, in English itself, but the main point still stands - it’s based on sound. In our language, you wouldn’t draw an image of a cat to represent a cat, you’d just write “cat” based on the sounds of the word. Here are the types of phonetic writing systems:

Alphabets

Alphabets work by having symbols for vowels and consonants, and they’re just written without really being treated as separate phonemes. These are arguably the simplest. Apart from the Latin alphabet, some others are Cyrillic, Greek, IPA, Georgian, Armenian, etc. Korean’s writing system, Hangeul, is kind of like an alphabet because it writes out its vowels and consonants, but it arranges each syllable into its own block. The word alphabet comes from the first to letters of Greek, alpha and beta.

Abjads

Most alphabets evolved from abjads. Abjads are like alphabets, except usually, most of the vowels aren’t written, and instead inferred from context. Only long vowels are written. Sometimes, for clarity, the short vowels may be written in with diacritics. For example, in the Quran, even though the Arabic script is an abjad, all the vowels were written so that there aren’t any misinterpretations. The word “abjad” comes from the first four letters of the Arabic script, “a”, “b”, “j”, and “d”, which is cognate with Greek’s “alpha”, “beta”, “gamma”, “delta”. The most prominent example of abjads are the orthographies of Semitic languages, which it works well for due to their triconsonantal root system, where consonants carry the meaning and vowels just modify the word. Hwvr, f y d ths n nglsh, t wll b prtt mssd p nd nt t ll ntllgbl.

Syllabaries

In syllabaries, each symbol is a syllable, usually a pair of consonant and vowel. These work well for languages that don’t have crazy consonant clusters, like Japanese and Cherokee. However, if a language has a lot of possible syllables due to its large phonology, then there would be way too many symbols.

Abugidas

Abugidas, in my opinion, are by far the coolest type of phonetic orthography. How it works is that if you write a consonant on its own, it comes with a vowel after it. For example, the /k/ sound in Devanagari, क, is actually pronounced /kə/ because without altering the consonant, it comes with an /ə/ sound. To make it a different vowel, you add a diacritic. So, /ke/ would be के. And, to make it just /k/ with no vowel, you make it क्. The most popular abugidas are from India, including Devanagiri, Tamil, Bengali, etc. However, the word “abugida” comes from the Ge’ez script from Ethiopia, where the first four letters are “a”, “bu”, “gi”, and “da” (and this arrangement is cognate with Greek’s “alpha”, “beta”, “gamma”, “delta”, just like with the word “Abjad”).

Semantic Orthographies

Instead of writing symbols based on sound, some languages have orthographies where symbols are based on meaning.

Logographies

The most common type of semantic writing system is a logography, and the most famous type of logography is Hanzi from Sinitic languages, which is also what Japanese’s Kanji is based on. For example, look at the symbol for “yi” in Mandarin or “ichi” in Japanese, which means “one”: “一” Now, for “er” in Mandarin or “ni” in Japanese, which means “two”: “二” So, sometimes, the symbol looks like what it means. However, sometimes, it can be more complicated than that. In Mandarin, each symbol is generally one syllable as well, and sometimes symbols are made based on their relation with other semantic meanings, so you can build up symbols from smaller symbols. For example, the symbol for “forest” is 森, and the symbol for “tree” is 木. Also, symbols whose words sound similar can also be used for clarification. Egyptian hieroglyphs were part logography. Some symbols worked just like Chinese, and others evolved into more of a syllabary or abjad.

Pictographies

Pictographies are kind of like logographies, except that it’s much more literal. Unlike Hanzi, where a lot of characters are derived from abstract connections, pictographies are literal depictions. This is likely where writing started first. An example is the Mayan script, where a lot of it was pictographic, but other symbols evolved into being logographic or syllabic. Also, even emojis are largely pictographic. However, pictographs, like logographs, still just represent words.

Ideographies

Ideographies are another type of semantic orthography, where an idea or a concept is directly written, without being tied to a specific sound. For example, some street signs symbols that don’t have words but rather symbols, some of the more ancient Hanzi initially, or even some of the more abstract emojis as well are ideographies.

Evolution of writing

Many writing systems evolved from Egyptian hieroglyphs, to become primarily alphabets, abjads, or even abugidas. This is primarily in Europe, the Middle East, and North Africa, where Egypt indirectly influenced. For example, the European alphabets evolved from Ancient Greek’s alphabet (Latin through the Etruscan alphabet, which in turn came from the Ancient Greek alphabet), which evolved from Phoenecian’s abjad, which evolved from Egyptian hieroglyphs. Also, the Semitic abjads evolved from Phoenician’s abjad too. The Semitic languages are written from right to left, because it chose a direction to write from Phoenecian, which alternated. Ancient Greek also initially alternated directions line by line, but then chose to stick with only left to right, which all the European languages are written with now.

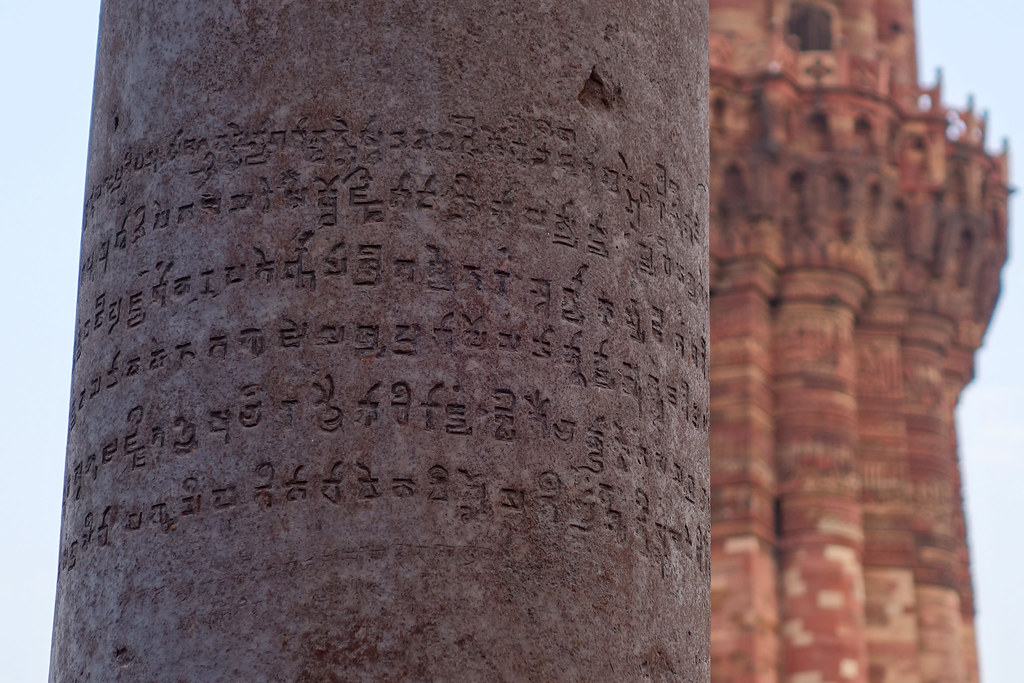

In India, as well as some parts of Southeast Asia, including Myanmar, Laos, and Thailand, the orthography (all abugidas) of those languages evolved from the Brahmi script, which was an abugida. It’s not certain where the Brahmi script is from, though it’s suggested to come from Egyptian hieroglyphs too, but it could also be an artificially created script that evolved naturally.

The Brahmi script was initially all straight lines and sharp angles. In South India, Southeast Asia, and Sri Lanka, the letters look more curvy, because they were written on leaves, so sharp turns and straight lines would tear the leaves. However, in North India, the letters can be more angular and sharp, but still also some curves, because they were written on both leaves and stone.

In China and Japan, the characters are derived from the Ancient Chinese logographic characters. In Japan, there are three writing systems. Two are syllabaries derived from Chinese, and the other is the normal Chinese logography.

In both Koreas, Hangeul is used. Hangeul is an artificially created script that was made to address the high percentage of illiteracy, due to the fact that Chinese characters were way to hard for the common people to learn. However, Hangeul was designed to be very simple.

The Cherokee syllabary was made after one Native American looked at the European colonizers’ writing and tried to mimic the symbols to make a writing system for Cherokee. He’d seen both the Latin and Cyrillic scripts. However, the symbols in Cherokee that look similar to the European writing make completely different sounds, as he only knew the shape of the symbols, not what sound they made.

To Be Continued

OK, that phonetic writing system stuff was cool, but you need to know how sounds actually work to use the symbols that represent them. How does that work? Wait until next time to find out!