Introduction

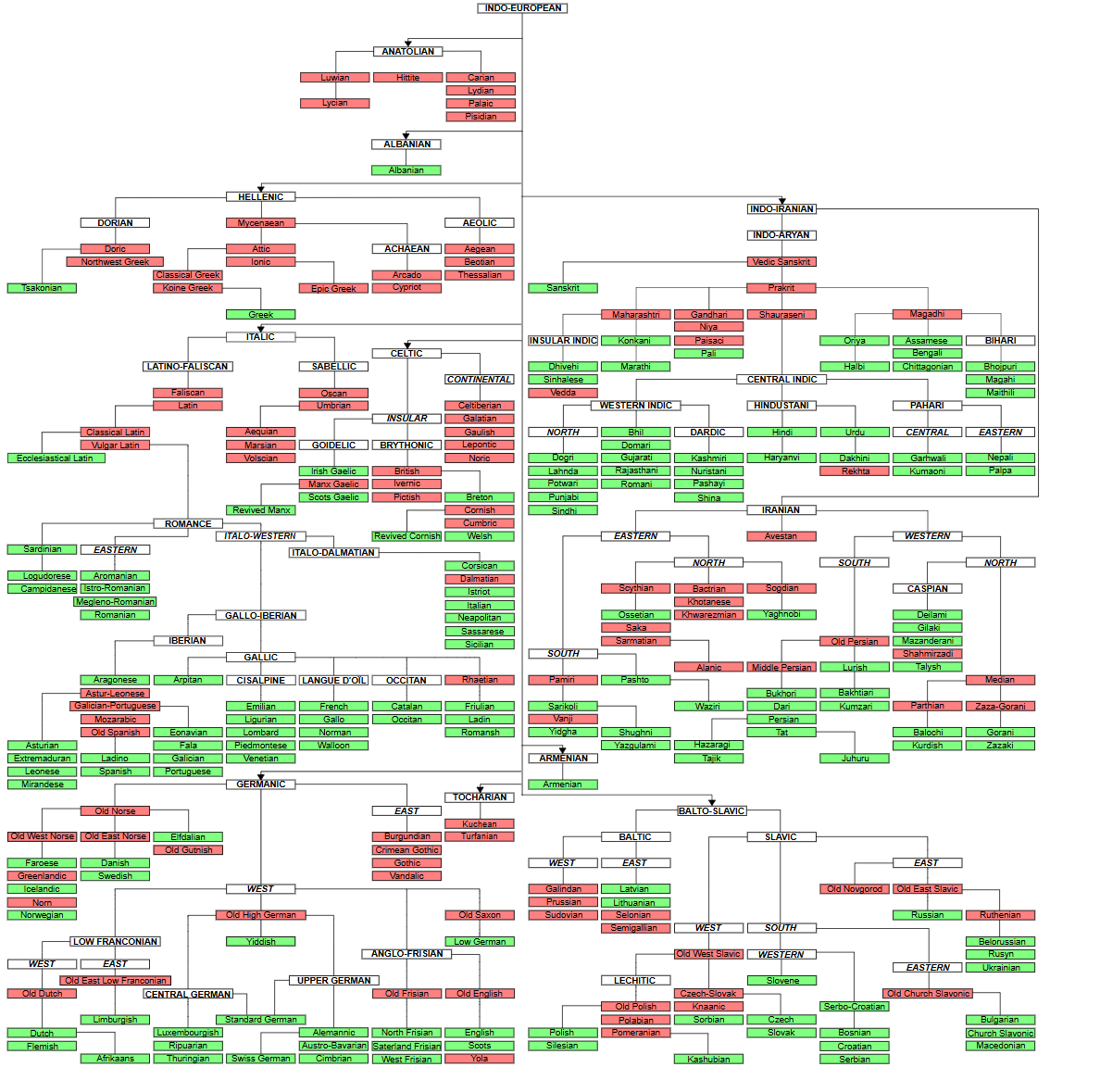

Right now, I’m jumping around the circle of linguistics a little. The trend has been to go from smaller units of language to bigger ones, like sounds to words to sentences. However, I think that going to one of the outermost rings, with the units of languages and language families, is helpful for more context with the inner rings too.

Historical linguistics is basically how the field of linguistics started - it’s not like early linguists from the 1800’s were saying “Oh, cool, a new field just appeared with barely any competition! Let’s convert tokens to vectors in semantic space using trained embedding matrices!” On the contrary, they were just observing languages at a broader scale, and realized that there actually were patterns, trends, and rules about how they could be related. That’s when they realized that languages could be analyzed scientifically, and weren’t just random gobbledegook.

Historical context of historical linguistics

This first part is probably way too much information, but for the full context, here you go.

European Exploration

After “la Reconquista” in Spain and Portugal in the late 1400’s, where the Catholics kicked out the Ummayad Caliphate from the Iberian peninsula, they realized that they didn’t have to worry about being religiously persecuted for not being Muslim anymore. So, they made boats and set sail, to religiously persecute the rest of the world for not being Catholic. This is why the year Colombus reached the Americas and immediately started doing terrible things to the people there is the same year that “la Reconquista” finished.

After the Spanish and the Portuguese made sailing around the world popular, other Europeans joined in as well, like the Italians, the British, the Dutch, and the French. The thing that all these Europeans had in common is that they all spoke Indo-European languages.

All the Europeans mainly sought after India, as well as nearby places like Southeast Asia, to get some spices, probably because they were sick of bland food. However, there was one major problem with this: the Ottoman Empire occupied Turkiye as well as much of the area around it, and they didn’t let anyone cross; even if they did, they couldn’t cross by boat, since the Suez Canal hadn’t been invented yet. So, they had to sail all the way around Africa, which I doubt anyone these days would have the patience to do.

The discovery of Indo-European languages

Upon finally reaching India, many Europeans noticed similarities between the local Indian languages and their own European languages. You can also see this yourself - the Hindu god of fire’s name is “Agni”, and in English, we have the word “ignite”. “Ignite” is from Latin, which means the mostly Romance-speaking Europeans were likely able to notice this with Indian languages. This is where the concept of cognates came from - words in different languages that have a common ancestor.

Observations like these led the Europeans to hypothesize that all ancient European languages like Latin or Greek came from Sanskrit. At this point, the Europeans were very confused. They used to think that all languages were descended from Hebrew. Lots of fringe theories emerged from the discovery of Indo-European languages, like the idea that Germanic tribes were from Persia. I will probably talk about these theories in a future post, but for now, let’s just say that they would all make you want to cry.

Finally, a linguist from Germany figured out that Sanskrit, Latin, Greek, and many other languages were all descended from a common ancestor language, which he called “Proto-Indo-European”. To do this, he invented the comparative method, which is what we will talk about in the next post.

Warning About Cognates

You have to be really careful about cognates, because it could either be that the words really are similar and semantically related, they are false friends (which means that the words just coincidentally sound similar but don’t have a common ancestor), or they are loanwords, which means that one language borrowed the word from another, but this does not imply relatedness or ancestry.

An example of loanwords is when Korean uses “keikeu” for “cake”, but this doesn’t mean that Korean is a Germanic language; instead, it just means that Korean had to borrow from English because they didn’t have a word for “cake” before and they were exposed to Anglophone culture.

False friends are also especially sneaky. If you told a German friend “Ich will dir Gift geben”, which you think means “I want to give you gifts”, they would probably stop being friends with you and even call the authorities on you, because “Gift” in German means “poison”, and has no relation to the English word “gift”.

Sound Changes

To understand the comparative method that will be covered in the next post, we need to first understand sound changes. For example, the word for “water” in Latin is “aqua”, but in French, which is descended from it, it’s “eau”. We know that “eau” and “aqua” are cognates, because “eau” isn’t a loanword and it isn’t gibberish. How could sound changes have caused this to happen?

The main idea is that the /kʷ/ in “aqua” gradually turned into a /w/, since the /k/ sound got weakened, so it sounded more like /awa/. After that, the /w/ sound got weakened as well, and it sounded more like /au/. Finally, the /au/ sound got weakened to /o/, which is how we got “eau” (French also preserves its older spelling, which means at one point it really did used to sound something like “eeyeawoo”).

These sound changes are pretty regular in a single language or language family, and at least have patterns cross-linguistically. For example, it’s more likely for a /tʃ/ to emerge from a /t/ that is near an /i/ or a /j/ than the other way around, because of a trend called palatalization, which is why in Portuguese, the word for “milk” is “leite”, but is pronouned “leiche” (Portuguese preserves historical spelling like French does).

One of the most famous sound changes is Grimm’s law. It states that in Germanic languages (the transition from Proto-Indo-European to Proto-Germanic, to be exact), the /p/ sound that is found in other Indo-European languages turned into an /f/ sound, the /t/ sound was turned into a /θ/ sound, and the /k/ sound was turned into an /h/ sound. That’s why in English, we say “father”, “three”, and “heart”, while in the Vatican, Latin speakers say “pater”, “tres”, and “cor”. A small note is that the “th” in “father” is actually a /ð/ sound, not a /θ/ sound, but that’s because of a subsequent sound change after being its voiceless version.

To be continued

So we know how people discovered that languages were related. We also know how sound changes and cognates work. How did early linguists use this to figure out Proto-Indo-European, and use this same method for other proto languages? That’s what we will talk about in the next post.