Linear Algebra

Right now, you might be wondering: “Sir, what is this? I learned this in 4th grade! Isn’t linear algebra just graphing lines on the coordinate plane and solving equations?” NO! Linear algebra has almost nothing to do with that, at least in the beginning. Now, let’s get into actual linear algebra.

Vectors

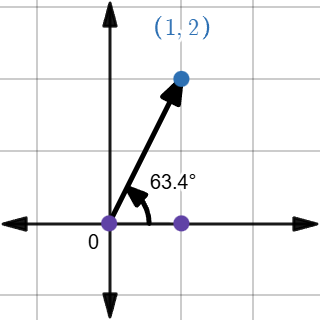

Vectors are basically the foundation of linear algebra. No, a vector is not named after the Despicable Me villain; it’s the other way around. A vector is, in short, an arrow in space, that you can think of as moving a point at its tail to its tip. In physics, you learn that a vector is a quantity with magnitude and direction. This means that the length of the vector matters, and so does the direction it points in. You can also represent a vector most abstractly, as a list of numbers. This is how computers view vectors. Each number tells the coordinate of each dimension of the arrow. For example, the vector \[ \begin{pmatrix} 1 \\ 2 \\ \end{pmatrix} \]

would represent a vector whose components are 1 unit in the \(x\) direction, and 2 units in the \(y\) direction:

In other words, it’s about \(2.236\) units long and points about \(63.435\) degrees measured counterclockwise from the x axis. Vectors can be multiplied by a number, also known as a scalar. This will scale, or stretch/shrink, the magnitude of the vector by the number. If the number is negative, the vector will be in the opposite direction. You can think of adding vectors \(A\) and \(B\) as first moving along \(A\), then from that ending point moving along \(B\). The original starting point to the new ending point will be the resultant vector. Similarly, you can compute \(A - B\) by scaling \(B\) by \(-1\). In terms of the components, you can just add each corresponding component, as this will be the net movement. For example, \[ \begin{pmatrix} 1 \\ 2 \\ \end{pmatrix} + \begin{pmatrix} 3 \\ 4 \\ \end{pmatrix} \]

will be

\[ \begin{pmatrix} 4 \\ 6 \\ \end{pmatrix} \]