This is a series of blogs about linguistics. Check out my ones about math, physics, and AI as well!

Phonetics And Phonology

How Sounds Work

At first, the question of “how do sounds work” may seem dumb - you just vibrate your vocal cords, right? However, it’s more complicated than that. When you were a baby, you were as educated as a linguistics major in that you were able to identify how different sounds are made from observing people’s mouths. Now, it’s more difficult to do so, and you may struggle - unless, of course, you’re a baby reading this, and in that case, you should become incredibly famous and win a world record if you haven’t already.

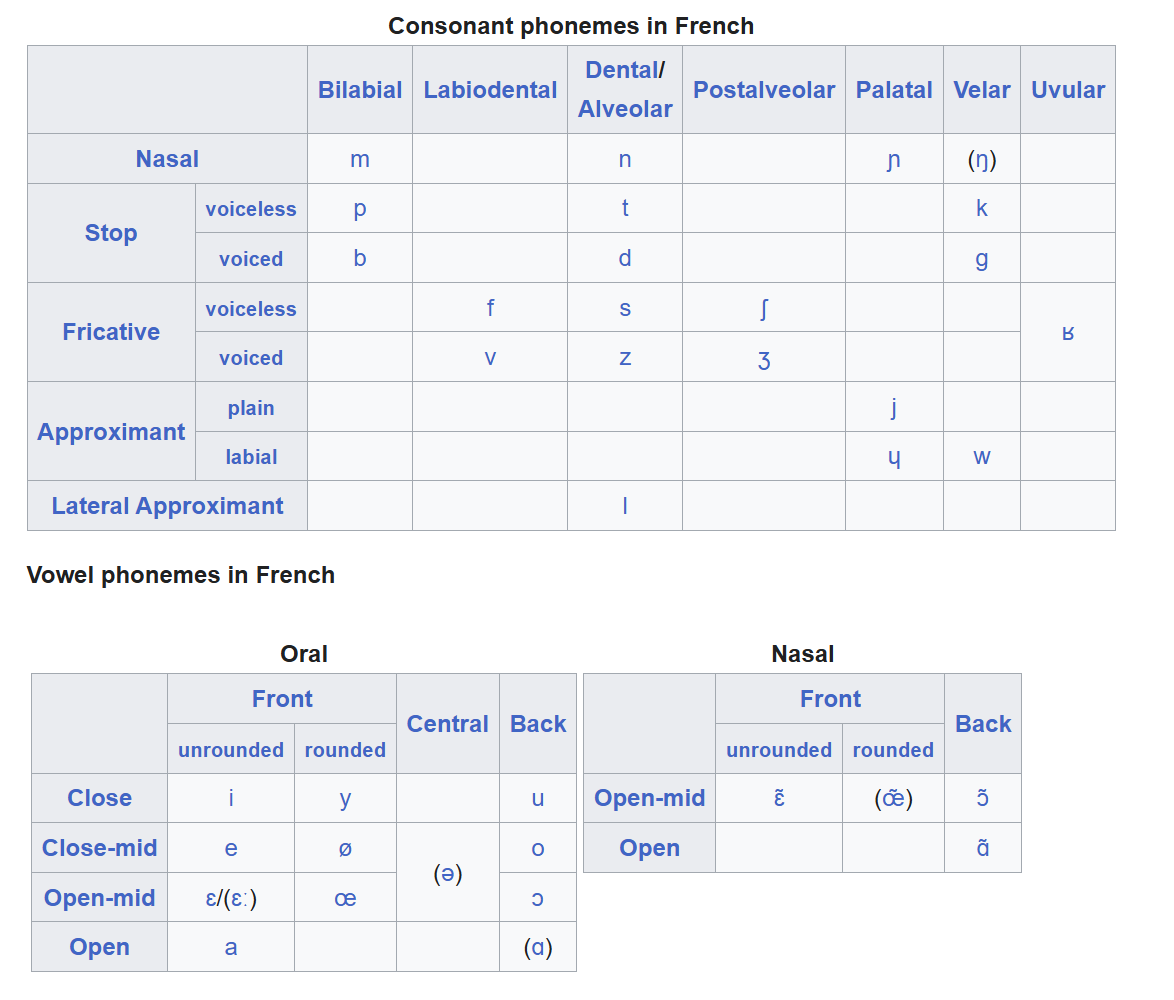

In kindergarten, you may have learned that sounds are classified as vowels and consonants, and that sounds are known as phonemes. However, I’ll talk about vowels later. Right now, let’s do consonants. In short, the two main parameters that control how a consonant is made are “place of articulation” and “manner of articulation”. ### Consonants #### Place of Articulation Place of articulation is essentially where in your mouth a sound is being made, whether it be deep in the throat (I’m looking at you, certain language primarily spoken in a country that borders Belgium, Germany, Luxembourg, Spain, Andorra, Monaco, Brazil, Suriname, and Italy) or front in the lips (like at the end of “dumb”). From deepest in the throat to closest in the lips, the most commonly referred to categories include glottal, pharyngeal, uvular, velar, retroflex, palatal, alveolar, dental, labiodental, and bilabial.

Manner of Articulation

Manner of articulation is how the sound is actually made. For example, there is a difference between “boron” and “moron”, even though both /b/ and /m/ are both “bilabial” sounds (one of the places of articulation mentioned above). Such manners of articulation include:

Fricatives (blowing air, like in the “sssss” sound in “snake”);

Plosives (stopping the sound, like how in “dart”, pronouncing both the /d/ and /t/ can’t really be continued);

Nasals (where air comes out of your “nnnnn-nostrils”);

Trills (where a sound is like a plosive but gets rolled, like the Spanish rolled r in “perro”);

Clicks (air is sucked in instead of pushed out, but unfortunately these cool sounds don’t exist in English, so I can’t provide an example you know how to pronounce. However, the name of the language Xhosa, (in)famous for having a lot of clicks, has a click in its name when not butchered as /kshosa/);

and more.

More

Another important parameter is voicedness. Voicedness is just if the vocal cords are vibrating while the sound is being made. To understand this, look at /s/ and /z/, or /k/ and /g/ (as an exercise, find the voiceless version of /b/). In most languages, this has a really important distinction. For example, take “tie” and “die”. However, we usually just include this within manner of articulation, because we can’t put 3D charts on the iPad screen your face is glued to.

Consonants are classified in other ways than just the two (or three) parameters, though. For example, there are pulmonic and non-pulmonic consonants. This just means if the sound is normal or a freak that doesn’t use air coming from the lungs. The only non-pulmonic consonants are implosives, ejectives, and clicks, and the rest are generally pulmonic. There is also sonorance or obstruence. Sonorance means the vocal tract is pretty open, like a vowel. As a result, most sonorants, which include nasals, approximants, and liquids, tend to be voiced. Obstruence means there is some friction or turbulence which make the sounds more easily voiceless and are noisier.

Additionally, there are more factors that can alter a consonant.

If you know Hindi, for example, you know how aspiration - putting extra air after a consonant - can impact a word and does matter, like in the words “पल” (pronounced like “pal”, meaning “moment”) and “फल” (pronounced like “phal”, meaning “fruit”).

In Russian, palatalization - making the consonant more like a palatal sound, which basically just makes it sound like “y” sound is at the end - is a very important factor too, with the words “мать” (pronounced like “maty” with the y being as in “yo” and not “corny”) meaning “mother” but “мат” (pronounced like “mat”) meaning a swear word.

Gemination - making a consonant pronounced for longer - is important in Finnish, because “tapa” means “way” or “manner”, but “tappa” means “kill”.

Vowels

Even in vowels, two main parameters affect how a vowel is made. While vowels are not that interesting in my opinion, they are definitely required, because without them you’d be speaking either gibberish or Polish. Vowels tend to be voiced because they are sonorant and made by vibrating the vocal cords.

The reason why whispering is quiet is because what you’re really doing is not vibrating your vocal cords at all. Since vowels are inherently voiced, by whispering, you end up not being able to project your voice very much at all, as vowels are kind of the base of speech.

The parameters are frontness (deep in the throat or front in the mouth) and closedness (is mouth open or closed). A third binary parameter is there, roundedness, which is if your mouth is shaped like a circle or not. For example, the /i/ sound is a closed front unrounded vowel.

There are many more variations to vowels that can be made now. For example, tone is a big factor in Mandarin. 糖 (táng) means sugar, but 汤 (tāng) means soup. Nasality (how much air comes out of the nostrils) is important in Fr*nch, as “a” means “has” but “an” means “year”. Rhoticity (how much the vowel sounds r-colored) makes the word “or” sound American when rhotic, but British when you only pronounce it like /oː/. Vowels can also have creaky or breathy voice (basically making it sound like a sheep or a zombie).

Vowel Harmony

Vowel harmony is a very cool property found in some languages.

Basically, all vowels in a word must be made with the same frontness, and sometimes closedness or roundedness too. ##### Example For example, in Kazakh, the plural marker is either “-лаp” or “-лер” (/lar/ or /ler/) depending on if the root of the noun is front or back.

“қала” (/qɑˈlɑ/), meaning “city”, uses back vowels, so “cities” is “қалалар”.

However, “көл” (/kœl/) meaning “lake”, uses front vowels, so “lakes” is “көлдер”.

Kazakh also has roundedness vowel harmony.

The IPA

Now that you know how sounds are made, let’s see how 𝚗̶𝚎̶𝚛̶𝚍̶𝚜̶ linguists actually write them. They made a chart called the International Phonetic Alphabet where each letter is consistent and makes the same sound all the time, because they are defined using the specific terms we talked about, like voiceless geminated bilabial trill (basically just horse noises). The IPA is kind of like the Periodic Table of linguistics. You may have noticed that throughout this article I’ve used slashes to refer to sounds. That was not just something random I did because a monkey walked on my keyboard one time and then I stuck with it - this is actually the notation of referencing IPA sounds.

Many letters are just like in English. For example, why don’t you take a random guess at how /p/, /h/, /v/, /z/, /m/, /ɪ/ and /t/ are pronounced? Yes! They are pronounced like “p”, “h”, “v”, “z”, “m”, “ɪ” and “t”! BUT NOT LIKE “pea”, “aich”, “vee”, “zee”, “em”, “eye”, and “tea” - you need to hop off elementary school English if you said that. And if you said “momentum”, “Planck’s constant”, “velocity”, “height coordinate”, “mass”, “current”, and “time”, hop off physics!

However, there are some tricky ones too that are designed to deceive you. For example, what sounds do you think /j/, /x/, /ɑ/, /r/, /q/, /c/, and /ʔ/ make? No, it is not “jay”, “eks”, “aey”, “ar”, “kyoo”, “see”, and “hmmm?”, or “impulse”, “position”, “acceleration”, “radius”, “charge”, “speed of light”, and “hmmm?”. Instead, they make the voiced palatal approximant, voiceless velar fricative, unrounded open back vowel, voiced alveolar trill, voiceless uvular stop, voiceless palatal stop, and the glottal stop (glottal stop doesn’t have a voiced version, because it’s just the break between “uh” and “oh” in “uh-oh”).

We’re not done. There’s even Greek letters, which somehow we can never evade, regardless of the subject. /ɸ/, /θ/, /ʎ/, /ɤ/, and /ʊ/ are not phi, theta, lambda, gamma, and upside-down omega, but instead voiceless bilabial fricative, voiceless alveolar fricative, voiced palatal lateral approximant, back close-mid unrounded vowel, and then this random vowel that doesn’t know where it belongs. Phew. That torture is over. Or is it?

We still have the diacritics to go over, but this time I won’t subject you to the pain of looking at every diacritic. Instead, I’ll just say that the diacritics can alter a sound to fit any of the variations for consonants and vowels I talked about earlier, such as nasality, gemination, voiceless, tone, and more.

To see the visual representation of the IPA, and to actually listen to their sounds, click here. Also, all the symbols and diacritics can be found here. Each language has its phonology written, by placing the accurate symbols of all of its phonemes. For example, see the phonology of Fr*nch.

To Be Continued

Phonemes, used by the IPA, are the building blocks of morphemes, which are the building blocks of words, sentences, and languages. However, I want to specify that phonemes are not usually connected to morphemes, as sound and meaning are generally independent. To talk about meaning, please stay tuned, unless you first want to deal with the PTSD of looking at the IPA.